Architectural Fees are a mystery to most people and there is no shortage of methods that architects use when charging for their services. How do you make sense of the options, which method works best for you, and how do you provide a method that suits the needs of both the architect and their clients.

Before we get into today’s topic, I should let everyone know that Andrew and I attended the International Builder’s Show and the Kitchen and Bath Industry show in Las Vegas from February 19 through February 22nd. I had some advisory board meetings to attend and Andrew came along because this is singularly the most amazing design and construction show in the country. We decided to take advantage of being in the same place at the same time and we recorded today’s podcast from inside one of the show homes that was built in the Professional Builder Show Village.

While recording was a bit more challenging than the relative peace and ease of recording in the front room of my house, it was definitely more exciting with considerably more energy and spectators. Maybe you didn’t know this but the ‘Life of an Architect‘ podcast is the official media partner with Building Design + Construction magazine and they also wanted to take advantage of Andrew and I being on site and in addition to having us record this week’s podcast on site, they also wanted to film it for other media blasts. I suppose this was technically our first live studio audience.

Part of what made this fun is that we were basically in a fishbowl with thousands of people walking around us, most of whom were peering in through the windows to see what was going on. Since the house we were in was a materials/product demonstration house, the entire objective is to expose visitors to new building materials and construction techniques. As a result, people were walking around while we were recording and pounding on the walls and stomping on the floors – which is apparently the only way to determine if those items are solidly built. You might hear us react to these “engagements” a few times in today’s episode.

Once we settled in, we had an excellent discussion on the many different ways architects charge for their professional services; hourly, percentage of construction, some combination of the two, a la carte based on specific phase of service (i.e. schematic design, design development, construction documentation, bidding and negotiation, and construction administration), or a cost per square foot of construction. To make things really interesting, a mixture of several of these fee structures could feasibly be combined. Is everything clear so far? No? That’s not surprising.

Hourly Fees [3:07 mark]

Just like it sounds – there will be an hourly chart for different level positions such as administration, drafting, project architect, partner, etc.) and you are charged that rate for the time spent. The main reason this format is used is when the scope of the work is not very comprehensive, unknown, or we have an existing client who prefers this method of billing. Generally speaking, most people don’t like being charged an hourly fee for fear of getting a surprise when the bill comes. As a result, when the work is charged hourly, we try and reduce concerns for the client by capping the amount or identifying financial milestones that indicate progress along the way.

Per-Square Foot Fees [7:54 mark]

I find this method unreliable and unreasonable. There are too many moving parts to assign a per-square-foot fee value to design and producing documents that could be used for bidding, permitting and construction. Since I mainly work on modern style projects, the amount of coordination I go through to detail a masonry building, things like sizing openings to align with the module of the selected masonry unit, water weeps, expansion joints, brick molds on windows, etc. versus the effort to work with a monolithic material like wood siding, or better yet, stucco, is disproportionate yet there is no doubt that this time spent saves money for the client – everything is cheaper to solve on paper than it is when you have a dozen people standing around the job site waiting for someone to figure this stuff out. The number of drawings required to properly coordinate one versus the other would not justify a single value cost. As a result, one of two things would most likely happen; since the fee would not be enough to compensate me for my time and overhead, either the quality of the drawings would diminish to reflect the fee, or I would be forced to work at a loss (which hopefully I would figure this out and either change my fees, cut corners, or go out of business). Everybody losses with this fee structure.

Combination Fees [10:35 mark]

I have an old boss of mine that loves this particular structure. Basically, it’s a combination of the hourly and the fixed fee. The schematic and design development portions of the project are hourly. This gives an incentive to the client to be available, make efficient, timely, and decisive decisions. It also protects the architect because regardless of the client, you know that you’re going to be compensated appropriately for your time. Some clients need to see iteration after iteration of possibilities, need a lot of counseling and reassurances, endless meeting, etc. and there’s no way to know beforehand.

When you move into construction documents, after having secured sign-offs on the designs along the way, the project has a more definable scope and a fixed fee can be used. Any changes to the design that are made during the construction drawings phase will need to be identified as an additional service and the fee reverts to the hourly rate schedule.

Once you are out of construction documents, the fee goes back to an hourly rate during the construction administration portion of the project. This way, the architect can be as available as the client wishes during this time period for project meetings, site visits, installation coordination’s, etc.

For me personally, I have a problem with the combination fee structure method because it rewards the incompetent architect for doing a bad job because there is a lack of accountability. Let’s say the client gives good instructions, a clear program, and an appropriate budget. If the architect doesn’t listen and has to produce multiple designs to get what the clients have requested, they still get paid their hourly rate. Continuing along, what happens if the architect prepares a poor set of construction drawings? They will be rewarded, again at their hourly rate, for the extra on-site coordination, preparing additional construction documents “requested” by the contractor, and for checking shop drawings for design work they didn’t resolve during the initial construction document phase. This is one of those instances where the system works with a competent, ethical architect; but fails miserably when you get something or someone else. If you were the client, how would you know ahead of time which one you were working with?

Percentage of Construction Fees [15:29 mark]

These percentages vary by firm but generally fall in the 8% to 15% range. This is our preferred method of determining our fee but one of the things that can always cause confusion is what exactly counts as part of the cost of construction. A good rule of thumb is to consider any scope where architectural coordination is required as part of the cost of construction. Seems pretty clear right? Well, we are just getting started; give me a chance to muddy the waters. We do not charge for coordinating other consultants scope of work, i.e. interior designers, landscape architects, pool design, exterior hardscape, etc. even though we spend a considerable amount of time and energy pulling their information into our documents and coordinating the design intent and construction requirements. We also do not charge for high-cost specialty items (like chandeliers) because the cost of the fixture is irrelevant to the amount of effort we spent to make sure that a junction box is provided for it in a specific location. It might as well be a surface mounted fixture from Home Depot. However, this is not true when it comes to kitchen appliances even though on the surface, they may seem no different to you than my chandelier analogy. A considerable amount of time is spent detailing and reviewing the cabinetry that surrounds the appliances and the specific trim out options and conditions they present. We also spend time selecting and presenting or evaluating the appliance packages with clients so there is coordination energy spent. Just read my post on the amount of time I have spent talking about the shape of ice cubes (here) and maybe you will get a better feel for it.

The Myth of Price Gouging [26:47 mark]

This is an understandable area of confusion and new clients routinely ask about the potential for us to increase our fees because we can specify expensive materials and drive the cost of construction up. There is an easy way for clients to quell these concerns; have a budget and tell your architect what it is up front. If we ever blow a stated budget when the construction bids come in, we will not charge the clients to redesign and redraw the project to get it back within the parameters established at the beginning. Where this area can get messy is when clients blow their own budgets, disregard our advice and continue moving forward with the documentation. I am constantly amazed at the successful and seemingly intelligent people who are surprised that the bid numbers are higher than the original budget when the house is 1,000 square feet larger than the original program. Did they think that there was a sale on square feet once you got over the 4,000? We might tell someone that the style and finish out of the house they want is tracking at $225 a square foot; therefore, if their budget is $1,000,000, that means approximately 4,450 square feet of a house. When the program they present is 5,000 square feet (I bet you know what’s coming next don’t you?), they will be over budget. Seems pretty obvious, doesn’t it? Apparently, it is not obvious to everyone.

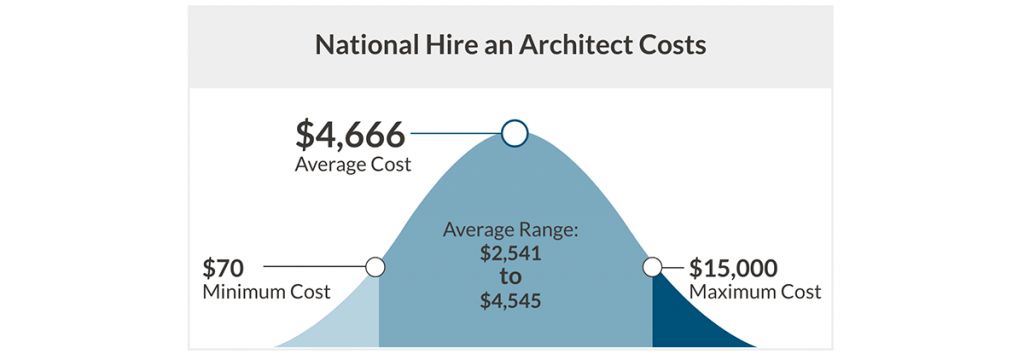

How Much Does the Internet Think an Architect Should Cost [36:23 mark]

All I can say about the above graphic is that it is one of the more amazingly stupid things I have ever seen in my life. Believe it or not, but, I actually spend time researching and preparing for the topics that I discuss on this site and one of the “research” methods I use is “what would someone who isn’t an architect look for” when it comes to finding information. In this case, I simply Googled “How much does it cost to hire an Architect” and this first return was the site where I collected the above graphic.

There is no data on this site to qualify what these fees represent so at best, this lack of information presents itself without any sort of qualifiers. Basically, if you want to hire an architect – for whatever reason – the price range is $70 to a maximum of $15,000 with an average of $4,666. This is categorically false information. Is it possible that someone could have this experience? I suppose it is possible but 25 years of work experience at almost ten different offices would lead me to believe otherwise.

This is yet another reason I hate the internet. If I took someone who has a yearly salary of $50,000, once I put an office overhead and operating multiplier of 2.8 ($50k x 2.8 = $140,000) divided by the number of billable hours in a year ($140,000 / 2,080) and I come up with $67.30 per hour … which is just under the $70 minimum cost or it translates in 69.3 hours worth of work … which is the AVERAGE.

For those of you who aren’t architects, do you think that someone can meet with you, identify all the moving parts and complexities to your project, design it, present and receive approval, move on to construction documentation where city minimum standards have been met for municipal approval, bidding and negotiation with potential contractors, and then perform construction observation of “x” number of months … all in 69.3 hours, a period of time just under 2 weeks of work?

I bet not.

[48:07 mark]

For this episode, we have a new hypothetical to consider. Here is the scenario:

Would you rather have to say everything that comes to mind, or never be say anything again?

Andrew thinks that I would die if I could never talk again – which is not true, pretty sure I wouldn’t die but I will admit that not speaking ever again would be an unpleasant proposition.

This post – and the podcast that goes along with it could easily have gone on for another hour so it seems likely that there will be a ‘Demystifying Architectural Fees – Part 2‘ at some point in the future – which is probably not a bad thing.