Every client wants to know what their project is going to cost and who’s going to build it. That means sending the drawings out and getting contractors involved … Let’s get ready to rumble because “The Construction Bid Process ” is today’s topic.

For those of you who might not know, a construction bid is the process in which the contractor takes the drawings and specifications as prepared by the architect and their consultants, reviews them for materials, quantities, and submits a price in which to undertake the scope of work as defined in those construction documents.

This should all sound pretty normal because this is what happens for any professional scope of service. I tell you what I want, you tell me what it’s going to take to give it to me, and I either agree or disagree to pay this price. In the construction world, it basically works the exact same way but there are some nuances and subtleties to discuss.

Let’s get into it and let’s start by discussing how projects are bid. I am going to start by stating that there is a difference between how public and private projects are bid but the basics are the same but there is a lot less formality and procedures for residential projects.

The bid process has several steps that are typically standard no matter what “delivery method” you are utilizing for your project. (We will get to those “delivery methods” in a future episode). So the basics of the bid process are as follows:

Step 1: Construction Docs Completed

The Architect and their team have completed a full set of construction documents that should include all of the important information required for contractors to provide a price to build the project.

Step 2: Advertise the Project (at large or to invited bidders)

During this period, the construction documents are provided to contractors and tradesmen to review, question, and price. This process can be handled in several ways depending (once again) on the delivery method. These days the majority of this process occurs electronically, though some forms of paper distribution still take place. The future for this step will be completely electronic at some point and may not even involve drawings.

Step 3: Bidding Q&A Period

During this step a set period of time is established, typically 3-4 weeks, that the documents are reviewed and such by anyone who hopes to provide a price to construct the work. This is directly tied to Step Two. The contractors can ask for clarifications or product substitutions or additional information within this set number of days. Also during this period it is the architect’s job to continue to distribute information to all those contractors who are bidding the work. This is always a set period of time, that once it ends, the pricing is due… the bid.

Step 4: Reception of Bids

So this is the step, usually an exact day and time, when everyone is required to provide their bid. Many times this is a frantic race to the end with bids coming in at the very last minute. The general contractor or construction manager assemble all of the trade bids they receive into a single number that is considered the price to build the project.

Step 5: Evaluation and Selection

This step involves reviewing all the bids and requirements of the bid documents by the owner, architect and other involved stakeholders if any. The goal here is typically to identify the best value for the project; this is not always the lowest bid. This review process is also ensures that the bidders meet all the requirements put forth in the request. It can also give time to get some clarifications on the bid number from the contractors. This part of the process varies again based on delivery method and the number of stakeholders in the project.

Step 6: Contract Negotiations & Start

This is the last one. At this point, bids have been evaluated and the contractor that is going to build the project has been chosen. Now, it typically becomes a large amount of paperwork. All the details and nuances of the legality of the contractual relationships are established during this step. Once this one is concluded, you can start construction!

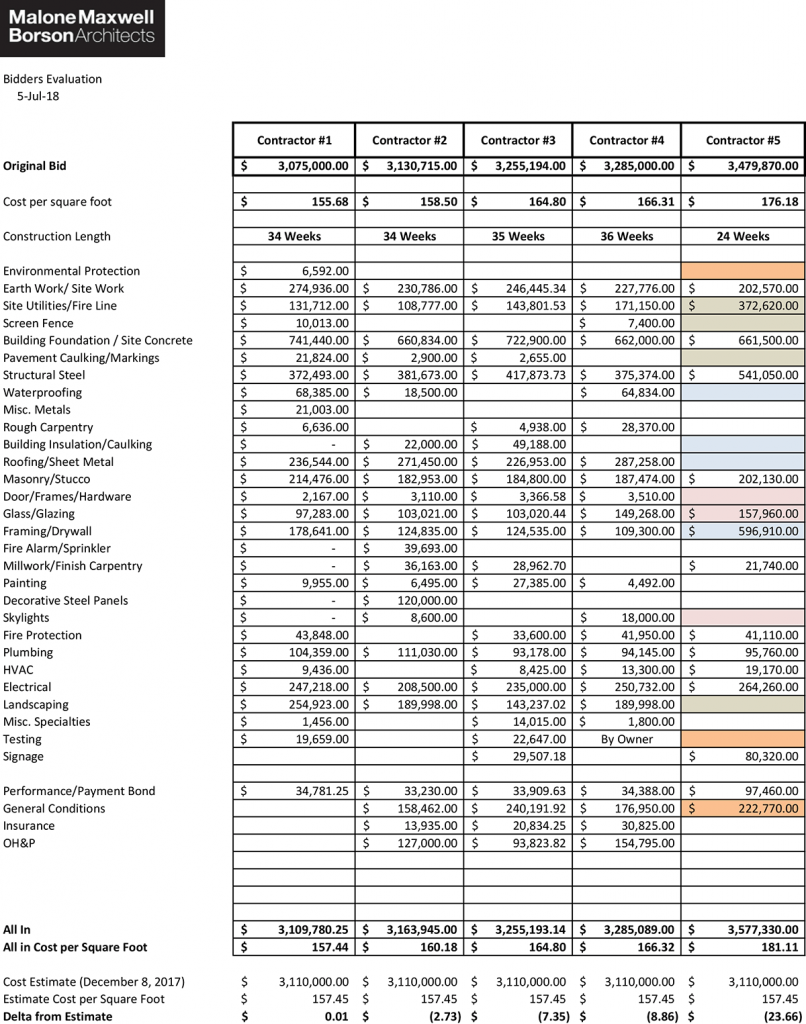

I thought for the sake of helping people visualize our conversation on bid forms that I would include a fairly simple version here for reference – this one is easy to follow and does not break the project down into too many different sections and categories. Whenever I send a project out for pricing or bidding, I always include some sort of form that helps break down an overall number into smaller and easier-to-process numbers. If you look at the very bottom of each column in this form, you will find an “All In” number for each contractor who submitted a bid, which typically includes all the information the contractor likes to pretend doesn’t really exist (taxes, insurance, required bonds, etc.)

It’s not that hard to imagine the difficulty of evaluating a $3,109,780.25 bid compared against a $3,163,945.00 (other than it being $54,164.75 lower) without having the other 33 rows of individual costs broken down into smaller amounts. Since I always build some version of this bid form into every single one of my projects that receives bids, it’s also not difficult to imagine why I want contractors to use my form and not one that they put together themselves. It is imperative that I get as close to an apples-to-apples comparison when evaluating costs … or why bother at all?

All it takes is a quick glance to see that of the 5 different contractors who submitted bids, not one of them actually followed my instructions and followed the form that I had provided. Seeing how I can’t completely eliminate the possibility that I might have sent a poor form to use, I would have to assume that the same gaps would have been put in place by everyone (i.e. providing a fire sprinkler category when there is no fire sprinkler) … which simply doesn’t happen. So the next step for me is to start calling everyone and asking them to do what they should have done in the first place – use my form. What you see above is the final product after a week of making calls and asking questions.

When I am feeling particularly frisky, I might even start color-coding the various categories when I have been able to deduce where money has been spread around but I don’t actually know HOW it’s been spread around. Whould you be surprised to learn that contractor #5 – which is the only one where color-coding was involved and has the most “gaps” in the bid form they were supposed to use – actually had the worst bid? Of course not.

The other advantage of requiring people to use my form is that it helps me identify where there are potential issues or mistakes. Gaps in the work provided are far more clearly identified when there is either a fee (and scope of work) missing or there were some wildly inaccurate numbers plugged in. For example:

- Look at the painting number provided by Contractor #3 – clearly, something is amiss here

- Look at the Landscaping number between Contractor’s 1 and 3 – huge discrepancy

- Finally, take a peek at Pavement Caulking / Markings … woah, Contractor #1 either screwed something up or put some other items in the category since they are 1,000% higher than the next closest bidder.

For what it’s worth, we ended up retaining the services of Contractor #3 because in the end, this is about the best value, not necessarily the lowest price.

[47:40 mark]

For this episode, we have a new hypothetical to consider. Here is the scenario:

If you could have one super power, what would it be, and could you avoid using this superpower for evil?

Evil might be a bit much but since demons aren’t involved, I am going to define evil as contrary to the public good. I posit that regardless of either your superpower or your predilections towards good, you will eventually try to leverage your superpower into making a better life for yourself … which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it’s just the first step to your eventual life of crime.

I’m going to go ahead and state the obvious and say that if you want to have a project successfully bid – regardless of the method you choose – it all comes back to the quality of the documentation. The more complete and thorough the drawings and specifications are at the time of bid, the more accurate the bid.